I had my second invertebrates practical today, and I got to practice my biological drawing (which I find oddly therapeutic). The organisms we looked at were from the phylum Annelida (comes from the Latin "ringed"), which are segmented worms. Not quite as cool a name as Platyhelminthes, the flatworms, but they can be equally as odd to look at. Phylum Annelida includes the lug worm, responsible for the nice squiggly sand patterns you see on the beach at low tide, and rag worms, commonly used as fishing bait.

The lab we were in had the faint smell of slightly mouldy fish, which was understandable considering all the specimens were dead and in trays under microscopes, right under our noses.

This looks like a plant, but it is in fact a worm, and it is apparently found only around cold hydrocarbon seep sites on the upper Louisiana Slope in the northern Gulf of Mexico and form groups of hundreds to thousands of individuals. These worms harbour internal chemoautotrophic sulphide-oxidising (thiotrophic) symbiont.

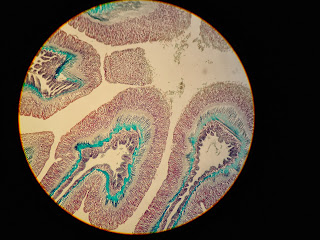

This was taken down a microscope (which is really quite hard to do well if you don't have an extremely steady hand), and it shows just how vast the size differences in segmented worms are. The picture below is a close-up shot, using the macro setting, of these worms. As you can see, they really are tiny- about 3mm long!

Here is the rag worm! this was a whopper, I think it was about 15cm long. These make up the majority of the worms farmed for the fishing bait industry. The picture below doesn't quite show the large, lethal looking jaws, but it does give some idea of how odd they look.

This rather cute thing is nicknamed the 'sea mouse', and you can see why. It is horribly difficult to draw biologically, as the only real feature you can see is hair, which you're not actually supposed to draw (because it's too much detail). My favourite part of this beauty is the iridescent hair round its sides.

This the organism responsible for the nice sand squiggles at low tide- the lug worm. It had a lovely set of gills, which looked like they were made out of shiny strips of copper. We learned last lecture that they build their casing by covering themselves in mucus and rolling around in their sand tunnel. Which quite frankly sounds disgusting.

This photo, again taken down a microscope, shows that the feature that defines Annelida, segmentation, can be really quite subtle. This specimen only shows a vague outline of its segments.

And here are my biological drawings from that practical:

In my ocean and earth systems lecture this morning, we learned about Snowball Earth, which has always been one of my favourite events in Earth's history. For those of you who haven't heard of it, it's a period of time in which Earth was completely covered in ice, and a series of volcanic eruption melted it back to what it is today. Snowball Earth is so significant because the reason why life survived the event was due to the properties of water- hydrogen bonding between water molecules makes it freeze less dense, resulting in ice being buoyant. Because it is buoyant, all the sea ice and glaciers developed on the surface, preserving and protecting life below the surface from the extreme temperatures above.

It's really quite incredible that hydrogen bonds saved all life about 2 billions years ago- without them, there might not be humans here today.

On that bombshell, I'll leave it at that. Goodbye!